The Story of MLPs

Wall Street told investors a simple story about master limited partnerships (MLPs) in midstream energy infrastructure projects: pipeline assets would generate a steady yield regardless of movements in the price of oil. MLPs seemed to offer a safer way to bet on the massive boom in domestic oil and gas production, a toll road rather than a commodity bet.

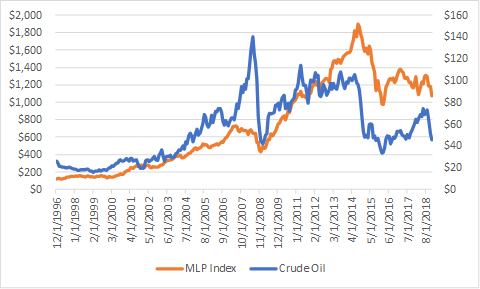

But this simple story didn’t exactly pan out. When oil prices fell 68% from 2014 to 2016, the MLP total return index dropped by about half. The correlation between the monthly change in the price of oil and the change in the MLP total return index spiked from 32% prior to 2014 to 52% since 2014.

Figure 1: MLPs vs. the Price of Oil

Source: Capital IQ, Alerian

What happened? Wall Street’s own enthusiasm—and effective marketing—sowed the seeds of a crash. The idea behind MLPs was so compelling that money poured into the asset class. There were 80 MLP and GP IPOs from 2010 to 2015, and 133 IPOs from 2001 to 2014, an average of one every five and a half weeks, according to data from Hinds Howard of MLPguy.com. This influx of capital led to a wave of pipeline construction. Prior to 2006, new pipeline construction averaged about $2B per year, but since 2006, new pipeline construction has averaged over $6B per year.

Figure 2: Capacity

Source: EIA

Total pipeline capacity expanded 42% from 2006 to 2017. This massive expansion of capacity, driven by massive investment by MLPs in new pipelines, caused the price of transporting oil to flatline.

Figure 3: PPI for Pipeline Transportation of Petroleum Products

Source: FRED

More investment created more competition, which drove prices down and return on capital lower—a classic parable of Wall Street bull-bear cycles. And enthusiastic investors didn’t differentiate the original MLPs, some of which were truly low-risk, high-quality assets, from a new wave of MLPs that were lower-quality business models. The earliest MLPs were long-haul interstate pipelines with 20-year fixed contracts, while many of the new MLPs were gathering systems in obscure shale plays with 3-5 year contracts. By the time of the massive drop in oil prices in 2015, the US market had been oversaturated with 50+ MLPs.

This is not even to mention the terrible financing structure that Wall Street bankers embedded in the MLPs they built, with incentive distribution rights that created a conflict of interest between the GP and the LP and encouraged leveraged expansion through acquisitions and new construction at the expense of free cash flow generation.

And, of course, pipeline volume is linked to oil prices. In the short term, volumes don’t fluctuate anywhere near as much as oil prices, but in the long term, demand for oil transportation depends on how much oil is drilled, which depends on the price of oil. And since terminal values, not today’s cash flows, are the biggest input into investors’ DCF models, MLPs turned out to be much more correlated to oil prices than sales pitches had suggested.

Investing is a game of meta-analysis, not a game of analysis. MLP prices fell because too many investors believed in the same story and their expectations exceeded reality. Today, many investors have been burned by MLPs, capital is scarcer, the financing terms are fairer to LPs, and the frenzy to build new pipelines has slowed. MLPs trade at more attractive valuations now because expectations are low and the problems with MLPs are transparent, just as the market was unattractive when expectations were high and nobody could find a reason why MLPs weren’t a great investment.

MLPs weren’t the safe income toll roads advertised to investors. The shale boom was real, but over-investment, high leverage, and increasingly low-quality assets combined to create a toxic brew for investors, many of whom had been drawn in by the promise of low risk and high current income. Sometimes the best stories mask the most dangerous investments.

Note: If you are interested in reading more about MLPs, I highly recommend two blogs, Hinds Howard’s MLP Guy and Simon Lack's US Midstream Energy Infrastructure Blog..