The MBA Indicator

MBA career choices are trendy and cyclical

By: Dan Rasmussen with Nicholas Rice

Readers of the New York Times were surprised to read that “the rich are not who we think they are.” The rich are more likely to be owners of banal regional businesses than Wall Street bankers, white-shoe lawyers, and Silicon Valley software developers.

A similar misconception seems to plague the decreasing number of newly minted MBA graduates, leading them to herd into fields with shiny reputations but lower likelihoods of creating great wealth. We studied almost 30 years of data on the career choices of MBA graduates of the Wharton School of Business. We looked at how their career choices varied over time, how those choices related to stock price performance of those industries, and how their choices compared to the Forbes 400 billionaire list. We cover the first two topics in part one this week, and we’ll look at the relationship between MBA choices and billionaire outcomes in part two next week.

Harvard Business School alumnus Ray Soifer famously coined the “Harvard MBA Indicator”: If more than 30% of Harvard MBAs choose "market-sensitive jobs" in the financial sector, this represents a long-term sell signal, while if less than 10% do so, it is a long-term buy signal. Indeed, we can see how the share of MBA graduates in tech and banking in particular has risen and fallen with those industries' share price performance.

This analysis provides insight into the aspirations and preferences of our managerial elite, and, perhaps, provides a few ideas for the professionals who seek to profit by going against the grain. The disparity between MBA and billionaire industry populations allows us to see the cyclical nature of the tech sector, the preference of MBAs for private equity over hedge funds, and the significant underrepresentation of MBAs in traditional industries like manufacturing, real estate, and retail.

In 2021, newly minted Wharton MBA crowded into a few popular fields. The below table shows which industries 2021 graduates entered, ranked by the share of the class.

Figure 1: Share of 2021 Wharton Graduates by Industry

Consulting27.2%Technology18.7%IB & Brokerage12.9%PE11.1%Healthcare, Pharma, and Biotech5.3%Investment Management3.7%VC3.4%Retail, Import & Export and Luxury Goods2.5%Insurance2.1%Real Estate & Construction2.1%Hedge Funds1.9%Telecommunications, Entertainment Media, and Sports1.6%Consumer Products, Food, Beverage, and Tobacco1.4%Manufacturing & Automotive1.4%FinTech1.2%Government, Social Impact, NFP, and Public Interest1.2%Energy & Utilities0.9%Legal & Professional Services0.9%Future Mobility0.5%

Source: Wharton MBA Career Reports

We can see changes in career preferences and industry popularity over time by comparing the 2021 industry choices to those of graduates in 2000.

Figure 2: Change in Wharton Graduates’ Industry Preferences (2000–2021)

Source: Wharton MBA Career Reports, Forbes 400 Lists

Private equity (+11.1%) and healthcare have been the biggest gainers. Banking, meanwhile, has been the biggest loser, with investment banking losing 8.8% share and commercial banking losing 1.9% share.

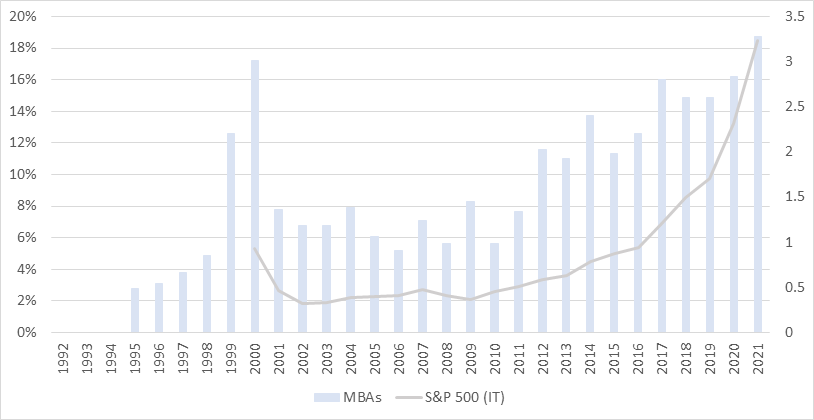

Technology, remarkably, is up from its 2000 peak. Soifer primarily applied his theory about the “Harvard MBA Indicator” to investment banking. But over the past 30 years, technology has been the more cyclical sector, with a mean year-on-year change of 13%. The below chart shows the strong correlation between the number of MBAs going into the technology sector and the sector’s stock price.

Figure 3: Correlation between Technology Sector MBAs and Stock Price

Source: S&P 500 Information Technology Sector (*Benchmarked to December 1999)

This doesn’t bode well for the Nasdaq!

Private equity’s rise is perhaps the biggest story in the MBA data. Private equity has become a site of pilgrimage for fledgling masters of the universe, with young MBAs hoping to enter the financial sector idolizing firms like Blackstone and KKR. The share of MBAs entering the field jumped from near 0% in 2000, to 1–6% from 2001-8, to 7–12% from 2009-21.

Figure 4: Share of Wharton MBAs Entering Private Equity (2000–2021)

Source: Wharton MBA Career Reports, Forbes 400 Lists

Technology and private equity have taken share from investment banking, a highly popular field in the 2000s that has lost its luster since the financial crisis. MBA numbers in investment banking went from a high of 30% in 2001 before the GFC, to 17.50% in 2009, to a low of just 11.80% by 2019. Competing data-driven explanations for this trend could also be that that Scorsese’s Wolf of Wall Street failed to resuscitate the pre-GFC sex appeal investment banking had back in 1987 when Tom Wolfe wrote The Bonfire of the Vanities.

Figure 5: Correlation between Banking Sector MBAs and Morgan Stanley’s Stock Price

Source: Wharton MBA Career Reports, Capital IQ

Even rallying share prices in recent years have not been enough to lure new MBAs. Several investment banks have reported that a talent squeeze across the industry has forced banks to offer higher pay and bonuses to attract and retain graduates for entry-level positions. Both the reputational damage of the GFC and the allure of a booming US tech sector have soured graduates on the investment banking pitch of big paychecks in exchange for long hours.

Wharton’s data provides insight into elite business trends: how private equity is increasingly seen as a golden ticket while MBAs scorn investment banking, how the attractiveness of technology has followed a boom-bust cycle, and how consulting has remained the post-MBA career of choice. Next week, in part two of this article, we’ll look at how the career choices of MBAs compare to the members of the Forbes 400 billionaire list.

Acknowledgment: This piece was co-authored by Nicholas Rice, a rising senior at Yale majoring in English and philosophy. He is looking for postgraduate roles in finance beginning in 2023.