Investing in a Bubble

Spotting Bubbles is Easier than Investing through Them

By: Ahmed Elbakari, Tom Macky, and Igor Vasilachi

The S&P 500 index soared 38% in 1995. This sharp increase, following four years of steady gains, made some of the smartest investors on Wall Street begin to grow wary of a bubble in the making.

Over the past few months, we studied what today’s most famous investors were saying during the years leading up to the dot-com bubble. We referred to investors’ letters to shareholders, online databases such as LexisNexis, and business books to collect their quotes, building a database of every piece of macro commentary we could find. We found that the investors we studied almost all perceived the market to be in a bubble, but almost all of them were too early in making the call. It’s easier to predict what will happen, it turns out, than when it will happen.

“I think we're approaching a blow-off phase of the U.S. stock market,” Ray Dalio told Pension & Investments in 1995. “Price acceleration on the upside is preceding a significant correction—20% beginning over the next 18 months.” Peter Lynch echoed Dalio’s concerns in an article in Worth Magazine in 1995, warning that “not enough investors are worried.”

It didn’t take long for more of the world’s top investors to start worrying along with Dalio and Lynch. In 1996, the S&P 500 soared another 23%, defying Dalio’s predictions of a quick correction. Describing the frenzied stock trading in 1996, Howard Marks wrote, “Every cocktail party guest and cab driver just wants to talk about hot stocks and funds.” And in his end-of-year letter, Seth Klarman expressed his concern with the public obsession with owning mutual funds and internet stocks: “We know the current mania will end badly; we do not know when.”

But US stocks continued their upward trajectory, with the NASDAQ rising 22% and the S&P 500 rising a whopping 33% in 1997. George Soros had seen enough, persuaded by the same fact pattern Lynch, Dalio, Marks, and Klarman had all observed. He decided to put on a significant short trade against US technology stocks.

By the end of 1998, Soros had lost $700m betting against internet firms, the fledgling titans of the new industrial revolution. Quantum, the flagship fund of the world's biggest hedge fund investment group, was suffering its worst ever year after a wrong call that the "internet bubble" was about to burst. Instead, companies such as Amazon.com and Yahoo! rose to all-time highs in April. Shawn Pattison, a group spokesman of Soros’s fund, said: "We called the bursting of the internet bubble too early."

In the five years from 1994 to 1999, the NASDAQ returned about 40% per year. The type of value investing practiced by greats like Howard Marks and Seth Klarman had been left in the dust, with annualized returns for the large-cap value index of only 24%. Warren Buffett’s Berkshire Hathaway had lagged the NASDAQ by 15% per year since 1994, forcing Buffett to explain why he didn’t hold AOL, Yahoo!, or any of the other hot technology names. He told CNN in 1999 that he “can't 'see' what technology businesses will look like in 10 years or who the market leaders will be.”

The broader public didn’t share Buffett’s concerns. In 1999 and 2000, there were 819 IPOs, day trading became a hot activity, and the NASDAQ rose 86% in 1999 and another 15% in the first months of 2000.

But in March 2000, five years after Dalio and Lynch first warned of a bubble, the NASDAQ turned a corner. What started with an announcement of rising interest rates by then Fed chairman Alan Greenspan—raising serious questions about the dot-com darlings' valuations and ability to repay debt—trickled into a market selloff, scandals of bad accounting practices, and major bankruptcies. By October 2002, the NASDAQ had fallen 75% from its peak, giving up all of its gains in the bubble and returning the index to 1996 levels.

Dalio, Lynch, Marks, Klarman, Soros, and Buffett had all spotted the bubble and warned investors of the dangers. But their foresight came too early. From 1995 until the peak in 2000, investors who favored international stocks, value stocks, bonds, or commodities had all lagged the NASDAQ by more than 20% per year. The below table shows the annualized returns of major stock indices, value indices, bond indices, and commodities from the first warnings of a bubble to the market’s peak in 2000.

Figure 1: Annualized Returns from First Bubble Warning (1995) to Peak (2000)

Source: Bloomberg, FRED, Ken French Data Library, Verdad

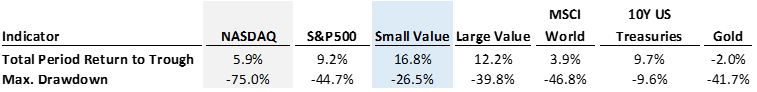

But by October 2002, two years from when the bubble burst, the picture looked dramatically different. Value emerged as the winner after the bubble, as a result of investors’ flight to safety to more traditional businesses, while 10Y US Treasuries ended up outperforming the once-raging growth equities. The table below shows annualized returns from the first bubble warning to the market’s 2002 trough.

Figure 2: Annualized Total Period Return and Drawdowns from First Bubble Warning (1995) to Trough (2002)

Source: Bloomberg, FRED, Ken French Data Library, Verdad

Value investing turned out to be the best strategy over this full period, according to our research. The bursting of the tech bubble restored the reputations of the great investors we studied, who generally outperformed the broader index by large margins from 1999 to 2002. But it took courage—and the ability to stick to a strategy despite lagging the market by wide margins for years—to achieve these outcomes.

That persistence and conviction might have been one of the key reasons for those investors’ long-term records and famous reputations today. But tolerating years of underperformance and missing out on big mark-to-market gains in a hot sector can be very painful. “Fear of missing out” is as powerful a force among investors as it is among social media influencers. In such environments, money managers face two critical hurdles. On one hand, a manager has a hard time convincingly denouncing an upcoming bubble when investors only see a market that is continuously creeping up. On the other hand, predicting a bust too early could result in adverse effects if the money manager is too wary. Investors do not want to pay fees to get their money parked for years while retail investors are riding the market and generating superior returns, even if the bubble is bound to burst at some point.

So what are investors that face these pressures to do? Would there have been a way to profit from the 1990s tech bubble but also get out before the market turned? Trend following offers one possible quantitative answer to the question. The idea of trend following is simple: own the asset as long as it’s going up, but sell and go into cash or bonds the minute the price falls below the 200-day moving average. Then buy the asset back again when the price moves above its 200-day moving average. The chart below compares the annualized returns from the first bubble warnings in 1995 to the peak in 2000 and to the trough in 2002, as well as max drawdowns, for the NASDAQ, S&P 500, small value, trend-followed NASDAQ, trend-followed S&P 500, and a 50%/50% combination small value and trend-followed S&P 500 and NASDAQ.

Figure 3: Annualized Total Period Return and Drawdowns from First Bubble Warnings (1995) to Peak (2000) and Trough (2002)

Source: Bloomberg, FRED, Ken French Data Library, Verdad

Trend following the major indices produced returns in line with small-cap value and significantly reduced the underperformance and drawdowns. Blending trend-followed indices with small-cap value produced similar results. Trend following worked effectively to follow the bubble up and get investors out before the full impact of the crisis was felt. Blending trend-followed indices with small-cap value produced an even smoother ride.

What are the lessons for investors today? It might seem that everything is different this time around. Warren Buffett now owns Amazon shares, and Howard Marks has referred to the bull market of the past decade, and growth stocks in particular, as “the new normal.” However, history shows that, much like gravity, market cycles are constant and can bend even the most resilient bull runs. With a stock market that has been growing unhindered since the aftermath of the global financial crisis, chances are high that the cycle might soon end, and investors should prepare. Some are voicing their concerns already. Bill Gross, who retired from active investing in 2019, is one of them: “An investor, not day trading on Robinhood, should begin to play defense,” he said in his investment outlook letter. He is joined by Jeremy Grantham, who stated in a recent interview with CNBC that he is more convinced than ever of a bubble in the stock market, adding that “the more spectacular the rise and the longer it goes, the more certainty one can have that you're in the 'Real McCoy' bubble.”

We don’t know who will end up being right, but we know that the markets are overvalued, and the conditions are present for a large selloff. In his letter to investors in 2018, Jeremy Grantham said, “We can be as certain as we ever get in stock market analysis that the current price of the market is exceptionally high. However, classic examples of the great bubbles of the past are not just characterized by higher-than-average prices. Price alone seems to me now to be by no means a sufficient sign of an impending bubble break.”

This ratio of growth to value valuations has already reached 1999 levels and is trending towards dot-com bubble levels. While this is not a definitive sign that we are in a bubble that is about to burst, it is yet another in a growing number of red flags. And while we believe value will prevail in the full sweep of history, those who want to participate in the bubble’s upside might want to consider implementing trend-following rules that might help cushion the fall if the large-cap technology market turns.

Acknowledgments: Ahmed Elbakari and Tom Macky interned with Verdad this fall. Ahmed is in his 2nd year at Stanford GSB and is looking to go into public market investing after graduation. Tom is a rising junior at Harvard studying economics. Igor has been working with Verdad since graduating from Stanford GSB in June, prior to which he worked at McKinsey & Co.